I’ll never forget the first time I harvested crisp lettuce from my garden in January. There I was, bundled in my winter coat, brushing snow off the cold frame lid to reveal perfectly green, tender leaves underneath.

My neighbor stopped mid-shovel to stare. “Wait—you’re still gardening?”

That moment changed everything. I realized winter doesn’t have to mean the end of fresh, homegrown food.

With the right approach, your garden can keep producing through the coldest months, delivering vegetables that actually taste better than their summer counterparts.

Why Winter Gardening Is Worth Your Time

Here’s what surprised me most: winter gardening requires less daily work than summer gardening.

Your plants grow slowly and steadily, watering is infrequent, and you’re not constantly battling weeds.

Once your crops are established and protected, they practically care for themselves. The secret isn’t fighting winter—it’s working with it.

Beyond the practical benefits, there’s something deeply satisfying about harvesting fresh food when your neighbors’ gardens are dormant.

You’ll save money on groceries, reduce food miles, and experience flavors that store-bought winter vegetables simply can’t match.

That first bite of frost-sweetened kale or candy-crisp carrot makes every bit of planning worthwhile.

How Plants Survive Winter: Understanding the Science

Cold-tolerant plants are remarkable survivors. When temperatures drop, they perform botanical magic: moving water out of their cells to prevent ice crystals from bursting them (this is what kills warm-season crops like tomatoes).

They also produce natural antifreeze—sugars and special proteins that lower the freezing point of their remaining cellular water. These sugars don’t just protect the plant; they’re what make winter vegetables taste sweeter after a frost.

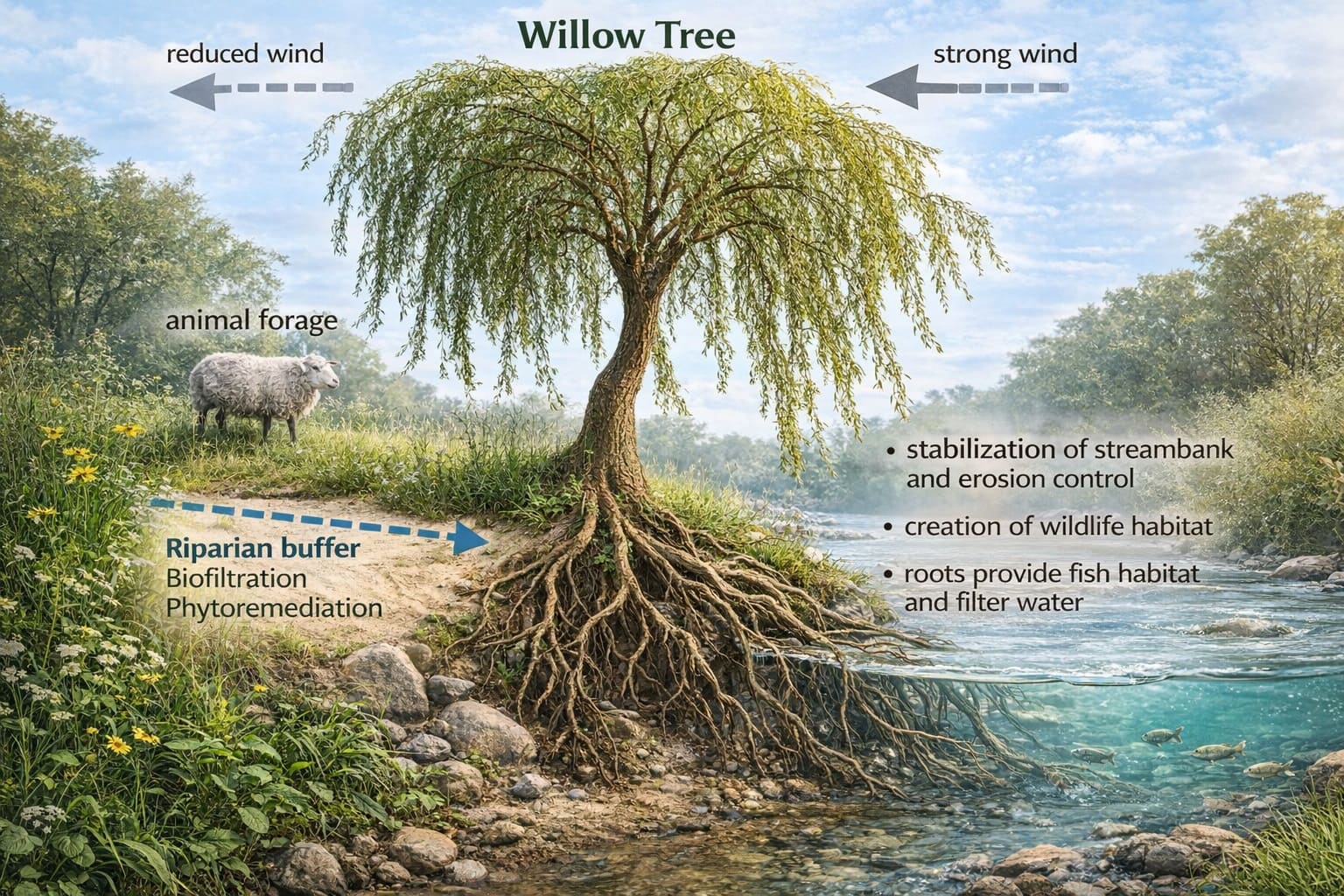

But here’s what most gardeners don’t realize: in most regions, extreme cold isn’t what kills hardy vegetables—it’s desiccation. Winter winds dry out plant tissues faster than frozen roots can replace the moisture, similar to freezer burn on food.

This is why protection from wind and maintaining soil moisture matters more than just keeping plants warm.

The Critical Timing Secret

This is where most winter gardeners stumble. Success depends on understanding one concept: the Persephone Period.

When daylight drops below 10 hours per day (roughly November through February in temperate zones), plant growth essentially stops.

Your vegetables enter dormancy, sitting in the garden like living storage. They won’t grow, but they won’t die either—if they’re mature enough and properly protected.

The key? Your crops must be mature or nearly mature before this period begins.

To calculate your planting dates, work backwards from your area’s first frost or when daylight drops below 10 hours. Check your seed packet for days to maturity, then add 7-10 extra days to account for slowing autumn growth.

For example, if winter lettuce takes 50 days to mature and your Persephone Period starts November 1st, plant in early September.

For longer-season crops like Brussels sprouts (90+ days) or storage cabbage (100+ days), you’ll be planting in midsummer.

I know—planning for winter while harvesting tomatoes feels strange, but this is what separates success from disappointment.

Choosing the Right Crops and Varieties

Not all vegetables tolerate cold equally, and variety selection matters tremendously. A summer lettuce variety planted for winter will bolt or freeze, while ‘Winter Density’ lettuce thrives in the same conditions.

The Ultra-Hardy Champions survive repeated freezing and thawing, handling temperatures into the teens Fahrenheit with minimal protection:

- Kale (‘Winterbor’, ‘Lacinato’, ‘Red Russian’)

- Spinach (‘Giant Winter’, ‘Space’)

- Mache (corn salad)

- Leeks

- Garlic (planted in fall for summer harvest)

- Parsnips (actually improve after freezing)

- Brussels sprouts

Cold-Tolerant Performers handle light to moderate frosts (mid-20s°F) with row cover or mulch protection:

- Carrots (‘Napoli’, ‘Bolero’ for best winter performance)

- Beets (‘Bull’s Blood’ for both roots and greens)

- Turnips and rutabagas

- Swiss chard

- Asian greens (mizuna, tatsoi, bok choy)

- Arugula

- Winter lettuce varieties (‘Winter Density’, ‘North Pole’, ‘Salanova’)

Here’s How to Grow Winter Radishes: Varieties, Planting Tips & Storage Guide

Here’s How to Grow Winter Radishes: Varieties, Planting Tips & Storage Guide

What NOT to Grow:

Resist the temptation to try warm-season crops—tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, squash, and beans need consistent warmth and won’t survive even with protection unless you have a heated greenhouse.

Even cold-hardy crops have their limits; standard cabbage varieties may bolt prematurely if planted at the wrong time.

When shopping for seeds, read descriptions carefully. Words like “winter,” “hardy,” “cold-tolerant,” and “bolt-resistant” are your clues. Seed companies often group winter varieties together, making selection easier.

Protection Strategies: Building Your Winter Garden Fortress

You don’t need an expensive heated greenhouse. Most effective protection methods cost less than a nice dinner out, and you can start simple and expand as you gain confidence.

Mulching: Your First Line of Defense

Think of mulch as a blanket for your soil. It insulates roots, moderates temperature swings, retains moisture, and keeps the ground workable longer.

Last winter, I mulched half my carrot bed with 6 inches of straw and left the other half bare. When temperatures hit 15°F, the unmulched carrots developed freeze damage. The mulched ones? Perfect.

Apply mulch after planting but before the ground freezes hard—typically late October through November in most zones.

For root crops like carrots, beets, and turnips, a 4-6 inch layer of straw, shredded leaves, or even pine needles keeps soil accessible for harvesting. For leafy greens, 2-3 inches is sufficient.

Row Covers: Lightweight Protection with Big Impact

These frost blankets float over crops on simple wire or PVC hoops, trapping heat while allowing light, air, and water through.

A medium-weight row cover (Agribon AG-30) provides about 4-6°F of protection. Double-layer it on especially cold nights for up to 10°F of protection.

I make hoops from 9-gauge wire bent into arches every 4 feet down the bed. The covers drape over these hoops and get anchored with rocks, boards, or garden stakes. Total cost for a 4×8 bed? About $30, and the materials last for years.

Credit: University of Maryland ExtensionCritical note: You must vent or remove covers when daytime temperatures rise above 40°F. Even in winter, a covered bed on a sunny day can hit 70°F inside, causing plants to lose their cold hardiness and triggering premature bolting.

Cold Frames: The Weekend Project

A cold frame is essentially a bottomless box with a transparent lid. The simplest version uses straw bales stacked in a rectangle with an old window laid on top.

I built my first permanent frame from scrap lumber and a recycled glass door for under $40, and it’s still producing five years later.

The magic happens on sunny days when the cold frame captures solar heat. On a January afternoon when it’s 25°F outside, my cold frame can reach 60°F inside—warm enough for active growth.

But this is also the challenge: you’ll need to prop the lid open on sunny days to prevent overheating, and close it again before sunset.

For maximum effectiveness, position cold frames on the south side of a building or fence to maximize sun exposure and provide wind protection.

Low Tunnels: Maximum Protection for Serious Growers

For dedicated winter production, low tunnels are hard to beat. These mini-greenhouses use metal hoops or bent PVC pipe covered with 6-mil UV-resistant greenhouse plastic installed over garden beds.

Plastic provides more insulation than fabric (up to 10-15°F protection) and creates a stable microclimate, but requires more management. You’ll need to:

- Vent on sunny days above 40°F to prevent excessive heat buildup

- Monitor for condensation (excessive moisture promotes disease)

- Remove snow accumulation before weight damages the structure

- Water when needed, as the plastic blocks rain

Think of low tunnels as “freeze-wrapping” your garden—you’re creating a protective microclimate that locks in humidity and blocks drying winds.

Soil Preparation: The Foundation of Winter Success

Winter vegetables need excellent soil, but preparation differs from summer gardening. The focus shifts to drainage and steady (not excessive) fertility.

Before planting, work in 2-3 inches of finished compost or well-aged manure. Winter crops are moderate feeders—they need nutrients for strong roots and healthy leaves, but excess nitrogen causes soft growth vulnerable to freeze damage.

I add compost plus a light application of balanced organic fertilizer (like 4-4-4) at planting time.

Drainage is critical. Waterlogged soil in winter leads to root rot and frost heaving. If water puddles after rain, work in additional compost or plant in raised beds. Many winter garden failures trace back to drainage problems, not cold.

For brassicas (cabbage family plants), test your soil pH. They prefer slightly alkaline conditions (pH 6.5-7.0) and may struggle in acidic soil. A simple $10 soil test can save you from months of disappointing results.

Water beds deeply a few days before planting, then let them settle. Pre-moistened soil gives seeds and transplants the best start. In fall, when temperatures are mild and rain is sporadic, maintaining consistent moisture is crucial for establishment.

Planting Your Winter Garden: Seeds vs. Transplants

- Direct sowing works best for:

Root vegetables (carrots, beets, radishes, turnips) that resent transplanting, plus quick-growing greens like arugula and spinach that can be sown multiple times for succession harvests.

- Start indoors as transplants:

Slower-growing crops like kale, cabbage, lettuce, and Asian greens benefit enormously from a head start. I sow these under lights in late summer, giving them 4-6 weeks to develop strong root systems before transplanting.

Here’s How to Cold Stratify Seeds: 4 Proven Methods That Actually Work

Here’s How to Cold Stratify Seeds: 4 Proven Methods That Actually Work

The Hardening Off Process You Cannot Skip

Seedlings started indoors or even in a protected area must be gradually acclimated to outdoor conditions—even cold-hardy crops. This process, called hardening off, typically takes 7-10 days.

Start by placing transplants outside in a protected spot for one hour on Day 1, bringing them back inside.

Increase outdoor time by 1-2 hours daily, gradually exposing them to direct sun and wind. By Day 7-10, they can stay out overnight and are ready for transplanting.

Skip this step and even “hardy” seedlings will suffer transplant shock, setting them back weeks or killing them outright. I learned this lesson the hard way with a flat of beautiful lettuce that turned to mush overnight.

Succession Planting for Continuous Harvests

Don’t sow all your lettuce at once. Plant a new batch every two weeks through late summer and early fall, stopping about 6 weeks before your Persephone Period begins.

This staggers your harvest so you’re eating fresh greens continuously rather than facing feast-or-famine.

I grow 24 lettuce heads at a time in three different varieties—enough for twice-weekly salads with some to share. When one planting matures, the next is already growing to fill the gap.

Container Growing for Winter: Small Space Solutions

Limited space or poor soil? Containers offer surprising winter potential, especially if you can move them to protected areas or bring them indoors during extreme cold.

Container requirements differ from summer:

- Insulation matters. Roots in containers freeze faster than in-ground plants. Wrap pots in bubble wrap or burlap, group containers together for mutual insulation, or move them against a south-facing wall.

- Drainage is crucial. Use containers with drainage holes and quality potting mix that won’t compact. Soggy soil + freezing temperatures = dead plants.

- Size appropriately. Leafy greens need 6-9 inches of depth, but kale and chard prefer 12-18 inches. Root vegetables like carrots need at least 12 inches.

Best container candidates include lettuce, arugula, spinach, Asian greens, radishes, and green onions. I keep a rotation of salad greens in 12-inch pots on my covered porch, moving them to the garage on the coldest nights.

Winter Garden Maintenance: The Surprising Truth

Once established, winter gardens need minimal intervention. This is gardening at its most meditative—checking on plants occasionally, harvesting as needed, with long stretches of simply letting nature do its work.

Watering Wisely in Winter

This is where many gardeners struggle. Your winter garden still needs water, but much less frequently and only when soil is dry several inches down.

Check moisture weekly, especially under covers that block rain and snow. Water in the morning on days when temperatures will rise above freezing, and always water the soil, not the leaves. Wet foliage in freezing temperatures invites disease.

- My approach:

I keep 5-gallon buckets in my garage, fill them the day before I need to water, and hand-water my beds. The water warms slightly overnight, reducing shock to plant roots.

- Critical point:

Water well before an expected hard freeze. Moist soil holds heat better than dry soil and protects roots. Counter-intuitive, but effective.

Here’s How to Build a Wicking Bed: DIY Self‑Watering Raised Garden Guide

Here’s How to Build a Wicking Bed: DIY Self‑Watering Raised Garden Guide

Feeding: Less is More

Winter vegetables don’t need constant fertilizing. The slow-release fertilizer applied at planting typically carries them through.

For greenhouse-grown crops or long-term container plants, a monthly dose of diluted liquid fertilizer (like fish emulsion at half-strength) maintains steady growth without promoting tender new leaves vulnerable to cold.

Monitoring for Pests and Problems

While pest pressure drops dramatically in winter, certain problems persist:

- Slugs and snails remain active in mild winter areas, especially under covers where condensation keeps things moist. Check regularly and handpick, or use organic iron phosphate baits.

- Aphids can explode under row covers and in cold frames where air circulation is limited. The solution is better ventilation on mild days and insecticidal soap if infestations develop.

- Rodents (voles, mice, rabbits) may discover your winter greens are the only fresh food around. Hardware cloth barriers or chicken wire cages protect valuable crops.

- Disease primarily means fungal issues from excessive moisture. Good ventilation and avoiding wet foliage solve most problems before they start.

Venting: The Management Task You Can’t Ignore

This deserves special emphasis because it’s the most common mistake I see winter gardeners make. Any covered structure—cold frame, low tunnel, or greenhouse—needs venting when temperatures rise.

- Here’s why:

On a 45°F day, a closed cold frame can hit 80°F inside within hours. This causes plants to lose their cold-hardening and triggers growth when you want dormancy.

Worse, warm humid air condensing on cold plastic or glass overnight creates perfect conditions for fungal disease.

- The solution is simple:

crack or remove covers when daytime highs will exceed 40°F, then close them again before sunset. I prop cold frame lids open with a stick and roll up the sides of my low tunnels a few inches.

In snowy regions, you’ll also need to brush snow off structures before the weight causes damage. A soft broom from the outside works well for plastic-covered tunnels.

Harvesting: Timing and Techniques

Harvest in the warmest part of the day when leaves are most pliable and sugars are highest.

For greens, I use the “cut-and-come-again” method—taking outer leaves while leaving the growing center intact. A single kale plant harvested this way can produce for 4-6 months.

Root vegetables can stay in the ground until needed, assuming your soil doesn’t freeze solid or you’ve mulched heavily.

In fact, many taste better with extended storage. I’ve harvested carrots in February that were sweeter than any I’ve ever bought.

Special harvesting notes:

- Harvest carrots, parsnips, and kale after a hard frost for maximum sweetness

- Pick lettuce and spinach before leaves get too large and tough

- Brussels sprouts actually improve after freezing—no need to rush them

- Cut greens in the morning if you’re storing them; they’ll keep longer

Learn When & How to Harvest Vegetables for Peak Flavor: Timing & Tips for Every Crop

Learn When & How to Harvest Vegetables for Peak Flavor: Timing & Tips for Every Crop

Beyond Fresh Eating: Winter Harvest Storage

Even with season extension, you may harvest more than you can eat fresh. Root vegetables store excellently with minimal processing.

- Refrigerator storage: Remove greens from roots (they draw moisture), store roots in perforated plastic bags in the crisper. Most keep 2-3 months this way.

- Cold storage: If you have an unheated garage, basement, or shed that stays 32-40°F, pack roots in boxes of barely damp sand. They’ll keep until spring.

- Freezing greens: Blanch kale, chard, and spinach for 2 minutes, shock in ice water, squeeze dry, and freeze in portions. Perfect for winter soups and smoothies.

- Leaving in the ground: This is my preferred method for carrots and parsnips. Heavy mulch keeps soil workable, and I harvest as needed. The garden becomes my outdoor refrigerator.

Regional Adaptations: Making Winter Gardening Work Where You Live

Mild Winter Zones (8-10)

You can grow almost anything through winter, including crops that flower like broccoli and cauliflower.

Your challenges are managing occasional heat spells and preventing bolt during warm periods.

Focus on succession planting and choosing bolt-resistant varieties. Simple row covers may be all you need for frost protection.

Moderate Winter Zones (6-7)

This is the sweet spot for winter gardening. With basic protection—mulch, row covers, or simple cold frames—you can harvest leafy greens, root crops, and hardy brassicas all winter.

Your strategy should focus on having crops mature by November, then managing ventilation and harvest through winter.

Cold Winter Zones (4-5)

Winter harvesting is challenging but achievable if you focus on the ultra-hardy crops and use substantial protection. Insulated cold frames, thick mulch, and multiple cover layers become necessary.

Your harvest window is shorter, but the satisfaction of eating homegrown spinach in February makes it worthwhile. Consider investing in a small unheated greenhouse for best results.

Very Cold Zones (3 and below)

You’ll need heated greenhouses for winter production, but you can still use fall extension techniques to push harvests well into November and start crops in February. Focus on storage crops and heavy mulching for spring revival.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

- Yellowing leaves: Usually nitrogen deficiency or waterlogged soil. Check drainage and consider a light feeding.

- Slow or no growth: Normal once you enter the Persephone Period. Your vegetables are dormant, not dying.

- Bolting (premature flowering): Caused by temperature fluctuations. Vent more aggressively on warm days to keep plants consistently cool.

- Frost damage despite protection: Layer up. Add second row cover, increase mulch depth, or add temporary covers on the coldest nights. Remember that desiccation from wind often looks like frost damage—better wind protection may be the answer.

- Mushy, rotting plants: Too much moisture. Improve ventilation and reduce watering frequency.

- Stunted plants that won’t grow: Planted too late, they’ll remain tiny until spring when they’ll likely bolt. Lesson learned for next year’s timing.

The Real Cost and Return

Let’s talk honestly about investment and payoff. A basic winter garden setup—row cover, hoops, and seeds—runs $50-100 for a 4×8 bed. A permanent cold frame costs $100-300 depending on materials.

Compare this to buying organic mixed greens at $6/container twice weekly December through March: $240+.

My winter garden produces roughly $500 worth of vegetables from a $200 investment (including seeds).

But the real value isn’t just monetary—it’s eating food at peak nutrition, reducing food miles, and having a winter hobby that gets me outside and active. You can’t put a price on satisfaction.

Start small if budget is tight. One mulched bed of spinach and one cold frame with lettuce costs about $60 and delivers enough greens for one person all winter.

Your Winter Garden Journey Starts Now

Winter vegetable growing isn’t about replicating summer abundance. It’s about working with the season’s rhythm, protecting hardy plants, and experiencing the satisfaction of harvesting fresh food when most gardens lie dormant.

That first winter harvest—whether it’s a handful of carrots or a bowl of crisp lettuce—changes how you see your garden. Y

ou’ll realize the growing season isn’t something that ends in October and resumes in May. It’s a year-round opportunity to connect with the earth and feed yourself.

Start simple: choose 2-3 crops from the ultra-hardy list, set up one protection method, and plant this coming late summer. Keep detailed notes about what works in your specific microclimate. Build on success gradually rather than attempting everything at once.

The vegetables are waiting. Your neighbor’s shocked face when you harvest lettuce in January? That’s waiting too. And once you taste that first frost-sweetened kale, you’ll understand why winter gardening isn’t just possible—it’s essential.

Ready to plan your winter garden? Drop a comment with your zone and which crop you’ll try first—I’d love to hear about your journey.

source https://harvestsavvy.com/growing-vegetables-in-winter/