Picture this: You’re walking through a tropical village when you notice basketball-sized, bumpy green fruits hanging from towering trees. A local grandmother approaches, cuts one open, and the aroma that escapes reminds you instantly of fresh-baked bread.

This is your first encounter with breadfruit—a fruit that has quietly sustained millions for over 3,000 years and might just hold keys to our planet’s food future.

What Is Breadfruit and Why Should You Care?

Breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) belongs to the same family as figs and jackfruit, but don’t let the “fruit” in its name fool you. When cooked, this starchy powerhouse tastes remarkably like potato crossed with freshly baked bread—hence its evocative name.

Native to the South Pacific, breadfruit trees are living grocery stores, producing 200-450 pounds of nutritious food annually for 50-100 years with minimal care.

What makes breadfruit extraordinary isn’t just its productivity—it’s the complete package. This gluten-free superfood delivers complex carbohydrates, complete protein with all nine essential amino acids, and impressive amounts of vitamin C, potassium, and fiber.

Yet despite feeding Pacific Islander communities for millennia, breadfruit remains largely unknown outside tropical regions.

Dr. Diane Ragone, director emeritus of the Breadfruit Institute, spent over 20 years collecting varieties from 50 Pacific islands. “Breadfruit has the potential to play a significant role in alleviating hunger in the tropics,” she explains. Her research has documented over 120 distinct cultivars, each adapted to specific growing conditions and culinary preferences.

Understanding Breadfruit Varieties: Choosing the Right Type

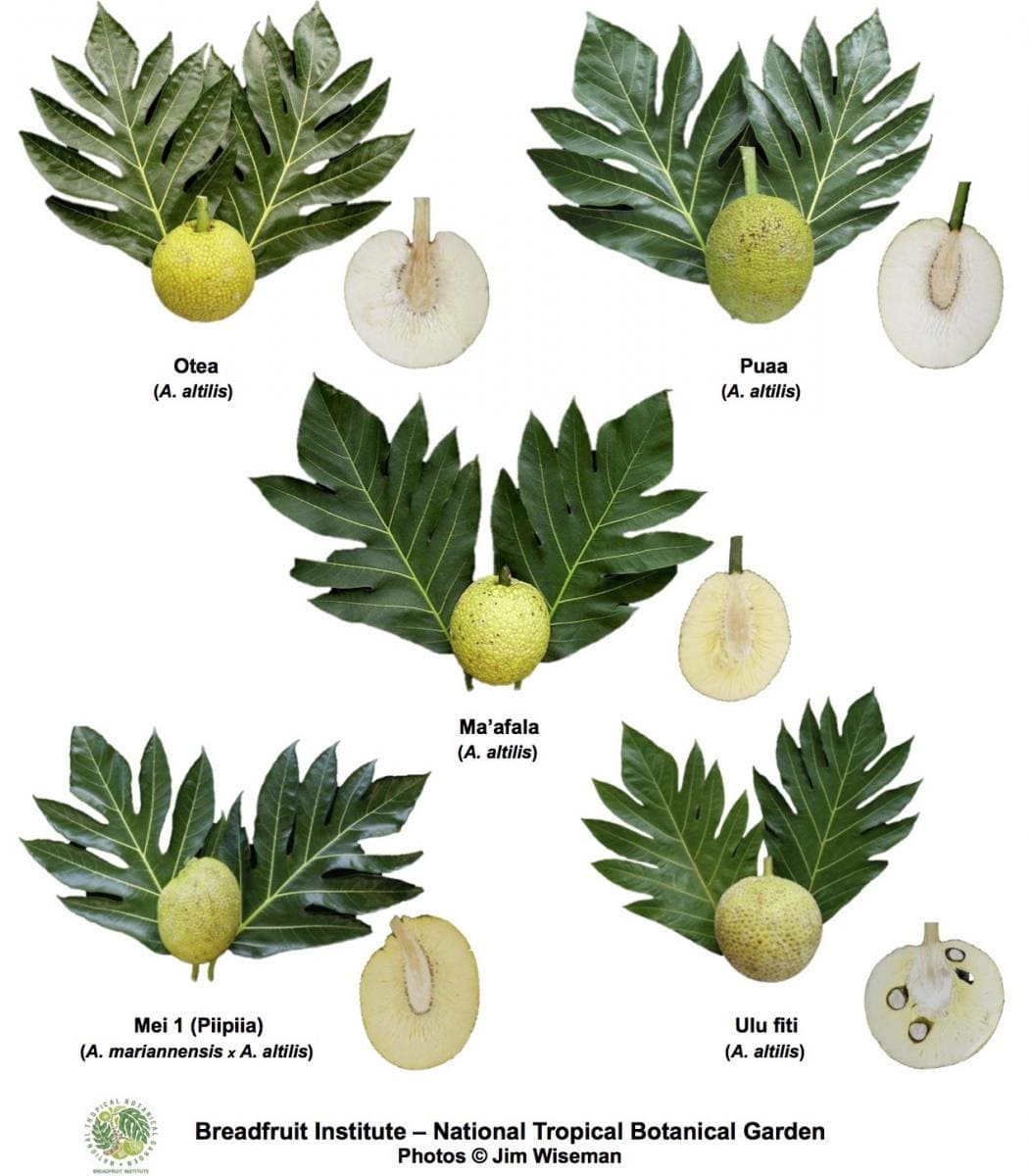

Most people don’t realize that breadfruit encompasses dozens of varieties, each with unique characteristics. Understanding these differences transforms breadfruit from mysterious tropical curiosity to practical culinary ingredient.

1. Seedless Varieties dominate commercial cultivation and include Ma’afala from Samoa, prized for its superior protein content that actually exceeds soybeans in essential amino acid composition.

Hawaiian ‘Ulu varieties tend to be larger and more starchy, perfect for poi-making, while Caribbean varieties like those descended from Captain Bligh’s introductions offer excellent all-purpose cooking qualities.

2. Seeded Varieties provide edible nuts along with the flesh. The Micronesian cultivars often show better salt tolerance, making them ideal for coastal plantings. These varieties typically have bumpier, more irregular skin textures and slightly different flavor profiles.

The choice matters more than you might expect. Ma’afala variety contains 12-15% protein compared to 3-4% in some Caribbean types, while certain Polynesian varieties contain up to 2,750 micrograms of beta-carotene per 100 grams—nearly three times the vitamin A precursors of sweet potatoes.

The Incredible Breadfruit Tree: Nature’s Most Generous Producer

A Living Marvel of Efficiency

Breadfruit trees grow 12-26 meters tall, making them among the world’s tallest fruit-producing trees. Their broad, deeply-lobed leaves create natural umbrellas, while their prolific output puts other crops to shame. A single mature tree can feed a family of four year-round—imagine having that level of food security growing in your backyard.

Recent yield studies from the Trees That Feed Foundation show remarkable productivity differences based on management. Traditional backyard trees in Jamaica average 25-50 fruits annually, while properly managed orchard systems in Hawaii achieve 150-300 fruits per tree. The difference lies in proper pruning, soil management, and variety selection.

The trees begin producing fruit just 3-5 years after planting and continue for decades. In Hawaiian tradition, families would plant a breadfruit tree when a child was born, ensuring lifelong sustenance. This practice, called “planting for the future,” reflects the deep wisdom of cultures that understood true sustainability.

Here’s How to Grow Cashew Trees: From Planting to Harvest and Enjoy These Nutritious Nuts

Here’s How to Grow Cashew Trees: From Planting to Harvest and Enjoy These Nutritious Nuts

Climate Champion with Proven Resilience

Recent research published in PLOS Climate reveals breadfruit’s remarkable resilience to climate change. While major crops like rice and wheat struggle with rising temperatures, breadfruit actually thrives.

The study, led by Northwestern University researchers, predicts that suitable growing areas for breadfruit will expand 4.1% in Asia and the Pacific under high-emission scenarios, while decreasing only 10-11% in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Perhaps more importantly, the research identified sub-Saharan Africa as having vast untapped potential for breadfruit cultivation. This is particularly significant since 70% of the world’s undernourished people live in regions suitable for breadfruit cultivation.

Mary McLaughlin from Trees That Feed Foundation has witnessed this resilience firsthand. After distributing over 90,000 trees across 44 countries since 2018, she notes, “We’ve seen breadfruit trees survive where other crops failed.

In Haiti, farmers told us breadfruit trees were producing food six months after Hurricane Matthew while their vegetable crops were still recovering.”

This climate resilience stems from breadfruit’s tropical origins and robust genetics. The trees can withstand droughts of 3-4 months once established, and their deep root systems prevent soil erosion. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, breadfruit trees were often the only ones left standing, regrowing from shoots within months.

Nutritional Powerhouse: The Science Behind the Superfood Claims

Comprehensive Nutritional Analysis

Breadfruit’s nutritional profile reads like a designer superfood, but the specifics vary significantly by variety and preparation method. A comprehensive analysis of Pacific varieties reveals remarkable diversity in nutritional content.

- Protein Quality Comparison:

The Ma’afala variety contains all nine essential amino acids in proportions superior to wheat, rice, corn, and even soybeans. Specifically, it provides 8.1% leucine, 4.2% isoleucine, and 5.8% valine—critical amino acids for muscle development and metabolic function.

- Vitamin and Mineral Density:

Fresh breadfruit provides 103 calories per 100 grams while delivering 25% of daily fiber needs and 32% of vitamin C requirements. More impressive is the mineral content—mature breadfruit contains 490mg of potassium per cup, comparable to bananas, plus significant amounts of magnesium (34mg) and phosphorus (43mg) essential for bone health.

- Glycemic Index Advantage:

Laboratory testing shows breadfruit’s glycemic index ranges from 48-68 depending on variety and preparation, significantly lower than white rice (73) or white potato (78).

This makes breadfruit particularly valuable for diabetes management—a crucial consideration in Pacific Island communities where diabetes rates have skyrocketed with dietary westernization.

- Antioxidant Powerhouse:

Seeded varieties contain extraordinary levels of carotenoids. Some Micronesian cultivars provide up to 939 micrograms of beta-carotene per 100 grams, while also delivering substantial lutein and zeaxanthin for eye health protection.

Traditional Medicine Meets Modern Science

Pacific Islander cultures have long used breadfruit medicinally, and modern research is validating their wisdom. Recent studies have identified anti-inflammatory compounds including flavonoids and phenolic acids that may help with joint pain and cardiovascular health.

Dr. Susan Murch from the University of British Columbia, who has extensively studied breadfruit’s bioactive compounds, notes, “We’ve identified over 70 phytochemicals in breadfruit, many with potential therapeutic properties. The traditional use of breadfruit leaves for treating diabetes and hypertension is showing scientific merit in our laboratory studies.”

Practical Shopping and Storage Guide

Selecting Quality Breadfruit

Walking into a Caribbean or Asian market for your first breadfruit purchase can feel overwhelming. Here’s your complete selection guide:

- For Cooking (Mature but Unripe): Choose fruits that feel heavy for their size with bright green skin showing minimal yellowing. The skin should yield slightly to firm pressure but not feel soft. Avoid fruits with black spots, which indicate overripeness or damage.

- For Sweet Applications (Ripe): Look for fruits with yellow-green to brown skin that gives to gentle pressure. The skin may show brown patches, which is normal. A sweet, fruity aroma indicates perfect ripeness for dessert preparations.

- Size Considerations: Breadfruits typically range from 1-8 pounds. Smaller fruits (1-2 pounds) are often sweeter and better for first-time cooks, while larger specimens (4-6 pounds) provide better value for families but require more planning for use.

Read the Ultimate Guide to Choosing Ripe Watermelons: Expert Tips and Tricks

Read the Ultimate Guide to Choosing Ripe Watermelons: Expert Tips and Tricks

Storage and Handling

- Short-term Storage: Unripe breadfruit keeps 2-3 days at room temperature or up to one week refrigerated in a plastic bag. Ripe fruit should be used within 1-2 days.

- Ripening Control: To accelerate ripening, place breadfruit in a paper bag with a banana. To slow ripening, refrigerate immediately after purchase.

- Safety First: Always wear gloves when handling fresh breadfruit. The latex sap can cause skin irritation and stains clothing permanently. Keep a bowl of salt water nearby while cutting to neutralize the latex on your knife.

Master-Level Cooking Guide: From Basic to Gourmet

Essential Preparation Techniques

The Latex Management System: Before cutting, let whole breadfruit drain stem-side down for several hours. Keep a bowl of salt water and multiple knives handy. When your knife gets sticky, dip it in salt water and switch to a clean blade. This simple system prevents the frustration that turns many people away from breadfruit cooking.

Core Removal Method: After peeling, locate the triangular core running through the center. Use a sharp knife to cut around it in a cone shape, similar to coring a pineapple. The core is fibrous and inedible, but the white flesh around it is perfectly good.

Step-by-Step Cooking Masterclass

Perfect Roasted Breadfruit (Serves 4-6)

Start with a 3-4 pound mature breadfruit. Score the skin in several places to prevent bursting, then place directly over an open flame or on a grill. Roast for 45-60 minutes, turning every 15 minutes until the skin is thoroughly blackened and a knife penetrates easily to the center.

The key indicator many miss: when properly roasted, the skin will crack and separate from the flesh. Let cool for 10 minutes, then peel away the charred skin to reveal perfectly steamed flesh underneath. The texture should be fluffy and slightly sweet, ready to eat with just a pat of butter and salt.

Breadfruit Mash with Island Flair (Serves 4)

Peel and core 2 pounds of breadfruit, cutting into 2-inch chunks. Boil in salted water for 25-30 minutes until fork-tender. Drain thoroughly—excess water creates gluey mash.

While hot, mash with 2 tablespoons coconut oil, 1 minced garlic clove, and salt to taste. For authentic Caribbean flavor, add 1 tablespoon lime juice and chopped chives. The finished mash should be creamy but not smooth, similar to rustic mashed potatoes.

Crispy Breadfruit Chips (Serves 2-4)

Use a mandoline or very sharp knife to slice unripe breadfruit into 1/8-inch rounds. Soak slices in salt water for 30 minutes to remove excess starch and reduce oil absorption.

Pat completely dry and fry in 350°F oil for 2-3 minutes until golden and crispy. The chips should curl slightly and sound hollow when tapped. Drain on paper towels and season immediately with salt, curry powder, or jerk seasoning.

Troubleshooting Common Cooking Problems

- Problem: Breadfruit turns mushy when boiled

Solution: You’ve overcooked it. Breadfruit should be fork-tender but still hold its shape. Start checking after 20 minutes and remove from heat when a knife slides in with light resistance.

- Problem: Bitter or astringent flavor

Solution: You’ve used unripe fruit or didn’t remove all the skin. Always peel completely and ensure the fruit has reached mature stage—the flesh should be white, not green-tinged.

- Problem: Latex makes preparation impossible

Solution: Next time, let the fruit drain longer and use the salt water technique. For immediate help, rub vegetable oil on your hands and knife to prevent sticking.

Learn about Harnessing Fig Sap For Natural Remedies, Vegan Cheese, and More

Learn about Harnessing Fig Sap For Natural Remedies, Vegan Cheese, and More

Advanced Processing: Making Breadfruit Flour and Preservation

Home-Scale Flour Production

Creating breadfruit flour at home requires patience but yields a versatile, gluten-free ingredient that stores for months. Here’s the complete process refined through years of Pacific Islander tradition:

- Step 1: Preparation and Drying

Select fully mature but firm breadfruit. Peel, core, and slice into 1/4-inch thick pieces. Traditional sun-drying takes 5-7 days, requiring daily turning and protection from rain. For faster results, use a food dehydrator at 135°F for 12-18 hours or oven-dry at lowest setting (170°F) for 8-12 hours.

- Step 2: Grinding and Sifting

Properly dried breadfruit pieces should snap cleanly and contain no soft spots. Grind in a high-powered blender or grain mill to fine powder. Sift through a fine mesh to remove any remaining large pieces. Store in airtight containers for up to 6 months.

- Flour Usage Tips:

Breadfruit flour absorbs more liquid than wheat flour. When substituting in recipes, use 3/4 cup breadfruit flour for every 1 cup wheat flour and increase liquid by 2-3 tablespoons. The flour works excellently in pancakes, muffins, and quick breads but lacks gluten for yeast breads unless combined with xanthan gum.

Traditional Fermentation Methods

Pacific Islander communities developed sophisticated fermentation techniques that transform breadfruit into long-lasting, nutritious food. The process creates beneficial probiotics while preserving the harvest for lean months.

- Modern Adaptation of Traditional Method:

Peel and core ripe breadfruit, then pack tightly in food-grade plastic containers with tight-fitting lids. The anaerobic environment encourages beneficial fermentation while preventing spoilage. After 2-3 months, the breadfruit develops a tangy, cheese-like flavor and can be stored for additional months.

Before use, rinse the fermented breadfruit to remove strong flavors, then mash with coconut milk or cook into stews. The fermentation process increases vitamin B12 content and creates beneficial probiotics for digestive health.

Growing Breadfruit: Complete Cultivation Guide

Site Selection and Soil Preparation

Successful breadfruit cultivation begins with proper site selection. The trees require well-draining soil with pH between 6.1-7.4 and protection from strong winds during establishment. Choose locations with morning sun but afternoon shade during the hottest months.

- Soil Amendment Protocol: Test soil pH and adjust with limestone if too acidic. Create planting holes 3 feet wide and 2 feet deep, amending with compost or aged manure. In heavy clay soils, plant on raised mounds to improve drainage.

- Spacing Considerations: Allow 30-40 feet between trees for full-sized varieties or 20-25 feet for dwarf cultivars. Breadfruit trees planted too close compete for nutrients and produce smaller yields.

Propagation Techniques for Success

- Root Cutting Method (Highest Success Rate)

During dormant season, locate healthy root shoots growing around mature trees. Dig carefully to expose roots 2-3 inches in diameter, then cut 8-10 inch sections with sharp, sterilized tools. Plant immediately in well-draining potting mix, keeping consistently moist but not waterlogged.

Success rates improve dramatically when root cuttings are treated with rooting hormone and placed in partially shaded locations. Expect new growth in 6-12 weeks, with transplant-ready plants developing in 8-12 months.

Here’s How to Propagate Plants in Water: Easy Step-by-Step Method

Here’s How to Propagate Plants in Water: Easy Step-by-Step Method

- Air Layering for Advanced Growers

Select healthy branches 1-2 inches in diameter and make shallow cuts in the bark. Apply rooting hormone, wrap with moist sphagnum moss, and cover with plastic film. Secure with ties and maintain moisture for 3-6 months until roots develop.

Timeline and Management Schedule

- Year 1: Focus on establishment with weekly watering during dry periods and monthly organic fertilizer applications. Protect from wind with stakes or temporary barriers.

- Years 2-3: Begin light pruning to develop strong branch structure. Apply balanced fertilizer (10-10-10) quarterly and maintain weed-free root zones.

- Years 4-5: First fruit production begins. Implement regular pruning schedule to maintain manageable height and improve air circulation.

- Years 6+: Full production phase with proper management yielding 50-200+ fruits annually depending on variety and care level.

Common Growing Problems and Solutions

- Leaf Drop and Yellowing: Usually indicates overwatering or poor drainage. Reduce watering frequency and improve soil drainage around root zone.

- Poor Fruit Set: Often caused by insufficient pollination or extreme weather during flowering. Hand pollination can improve yields in some varieties.

- Pest Management: Scale insects and mealybugs are common issues. Use horticultural oil sprays during cooler parts of the day and encourage beneficial insects with diverse plantings.

Economic Potential and Market Realities

Current Market Analysis

The global breadfruit market is experiencing unprecedented growth, driven by increasing demand for gluten-free alternatives and sustainable food sources. According to recent agricultural reports, breadfruit production has increased 23% in the Caribbean over the past five years, with Jamaica leading exports to North American markets.

- Price Points and Profitability: Fresh breadfruit currently sells for $2-5 per pound in U.S. specialty markets, while breadfruit flour commands $8-12 per pound. For small-scale farmers, a mature tree producing 100 fruits annually can generate $400-800 in gross income, making it competitive with traditional cash crops.

- Processing Opportunities: Value-added products offer the highest profit margins. Breadfruit chips retail for $6-8 per 4-ounce bag, while breadfruit beer and spirits are emerging premium market segments. Several Caribbean entrepreneurs have built successful businesses around breadfruit snack foods.

Investment and Development Trends

International development organizations are recognizing breadfruit’s potential for food security. The Trees That Feed Foundation has doubled its distribution annually since 2020, while the Breadfruit Institute has received increased funding for variety development and propagation research.

Private investment is following suit. Diana Chaves, founder of Jungle Foods in Costa Rica, reports difficulty meeting demand for her breadfruit chips: “We started with 30 farmers and now have contracts with over 200. The challenge isn’t finding markets—it’s scaling production fast enough.”

Environmental Impact and Sustainability Metrics

Carbon Sequestration and Environmental Benefits

Breadfruit trees excel as carbon sequestration agents while producing food. Research from the National Tropical Botanical Garden calculates that a mature breadfruit tree sequesters approximately 2.5 tons of CO2 over its lifetime while producing an estimated 15-20 tons of edible fruit.

- Comparative Environmental Analysis: Breadfruit production requires 98% less water per calorie than beef, 85% less than dairy, and 40% less than rice cultivation. The trees also improve soil health through leaf litter and root system enhancement, reducing erosion and building organic matter.

- Agroforestry Systems Performance: Studies from Costa Rican breadfruit agroforests show 35% higher biodiversity than monoculture plantations, supporting 60+ bird species and providing habitat for beneficial insects that reduce pest pressure on companion crops.

Dr. Noa Lincoln from the University of Hawaii’s breadfruit research program explains: “Breadfruit agroforestry systems represent a paradigm shift toward regenerative agriculture. We’re seeing carbon sequestration rates that exceed forest restoration projects while maintaining food production.”

Real-World Success Stories and Case Studies

Haiti’s Food Security Transformation

Following the 2010 earthquake, Trees That Feed Foundation partnered with local organizations to plant 15,000 breadfruit trees across Haiti. Five years later, communities report significant improvements in food security and nutrition.

Marie Fabiola, a farmer from Hinche, describes the impact: “Before breadfruit, we struggled to feed our children during dry seasons. Now my three trees provide enough food for my family plus extra to sell. My children are healthier and stronger.”

The program’s success led to expansion across 12 additional countries, with similar results in Ghana, Jamaica, and Guatemala. Communities with established breadfruit groves show 30% lower rates of childhood malnutrition compared to control areas.

Commercial Success in Samoa

The Ma’afala variety development in Samoa represents one of breadfruit’s greatest success stories. Originally selected for superior protein content, Ma’afala now supplies breadfruit flour to Hawaiian and California markets, generating significant income for Samoan farmers.

The Samoan Breadfruit Cooperative, established in 2018, now includes 150 farmer members who collectively process 20,000 pounds of breadfruit annually into flour, chips, and other products. Member farmer Tavita Faumui reports: “Breadfruit farming allowed me to send my children to university. This ancient crop secured our modern future.”

Urban Agriculture Applications

Miami’s Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden has pioneered urban breadfruit cultivation, demonstrating the tree’s potential for city food systems. Their compact variety trials show promising results for container growing and small-space cultivation.

“We’re seeing dwarf varieties produce 25-40 fruits annually in large containers,” explains Dr. Richard Campbell, the garden’s curator. “This opens possibilities for urban food production that we’re just beginning to explore.”

Tools, Resources, and Getting Started

Essential Equipment for Breadfruit Preparation

- Kitchen Tools: Invest in a high-quality chef’s knife (8-10 inch), mandoline slicer for chips, and large cutting board designated for breadfruit use. Keep multiple cheap paring knives for latex-sticky cutting work.

- Specialized Items: Food-grade gloves, small bowls for salt water rinses, and a sturdy peeler make preparation much easier. For serious cooking, consider a food dehydrator for making chips and flour.

Reliable Sources and Suppliers

- Fresh Breadfruit: Caribbean markets in major cities, Asian grocery stores, and online suppliers like Miami Fruit and Melissa’s Produce offer seasonal fresh breadfruit shipping nationwide.

- Seeds and Plants: The Trees That Feed Foundation provides planting materials for qualifying locations. Commercial nurseries in Florida and Hawaii offer breadfruit trees for subtropical growing zones.

- Processed Products: Breadfruit flour from Island Fresh and Grace Foods, chips from various Caribbean brands, and frozen breadfruit from Goya provide convenient introduction options.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q: How do I know if breadfruit is cooked properly?

A: Properly cooked breadfruit should be fork-tender but not mushy, similar to a perfectly baked potato. The flesh should be fluffy white or pale yellow with no hard or green areas remaining. Undercooked breadfruit will be starchy and difficult to digest.

- Q: Can breadfruit be frozen for long-term storage?

A: Yes, but texture changes significantly. Cooked breadfruit freezes better than raw. Cut into serving portions, blanch for 2-3 minutes, cool completely, then freeze in airtight containers for up to 6 months. Frozen breadfruit works well in stews and mashed preparations.

- Q: Is breadfruit safe for people with tree nut allergies?

A: Despite the name “breadnut” for some varieties, breadfruit is not a tree nut and is generally safe for people with tree nut allergies. However, those with fig or mulberry allergies should exercise caution, as breadfruit belongs to the same botanical family.

- Q: How long does it take to see fruit from a newly planted tree?

A: Breadfruit trees typically begin producing fruit 3-5 years after planting, with full production starting around year 6-8. Grafted trees may fruit earlier than those grown from root cuttings.

- Q: What’s the difference between breadfruit and jackfruit?

A: While related, they’re distinct species. Breadfruit is typically seedless, has smoother skin, and is usually cooked before eating. Jackfruit is larger, has spikier skin, contains many seeds, and can be eaten raw when ripe. Their flavors and culinary uses differ significantly.

- Q: Can I grow breadfruit in containers in temperate climates?

A: Dwarf varieties can survive in large containers (100+ gallons) in greenhouse conditions, but they won’t fruit reliably without tropical temperatures year-round. Container plants work better as ornamental specimens in temperate zones.

The Bottom Line: A Fruit for the Future

Breadfruit represents more than just another tropical curiosity—it’s a glimpse into a more sustainable, resilient food future. This ancient crop combines impressive nutrition, environmental benefits, and climate resilience in ways that could transform how we think about feeding the world.

As climate change challenges conventional agriculture, breadfruit stands ready to nourish communities across the global tropics. From its Pacific origins to its potential role in African food security, breadfruit proves that sometimes the best solutions for tomorrow’s problems have been growing right in front of us all along.

The transformation from obscure tropical fruit to potential global food solution requires action from individuals, communities, and institutions.

Whether you’re trying your first breadfruit recipe, supporting organizations that plant trees in food-insecure regions, or advocating for agricultural research funding, every action contributes to breadfruit’s expanding impact.

Consider the remarkable journey of this single species: from feeding Pacific Islander voyagers across vast ocean distances to potentially securing food systems for billions facing climate uncertainty. That journey continues with each person who discovers breadfruit’s potential and shares its story.

Your breadfruit journey starts with a single taste. Whether you’re trying your first breadfruit chip or planting a tree for the next generation, you’re participating in a food revolution that spans millennia.

The question isn’t whether breadfruit will play a role in our sustainable future—it’s how big that role will be, and what part you’ll play in making it happen.

Ready to explore breadfruit for yourself? Start by visiting a local Caribbean or Asian market to find fresh or canned breadfruit, then share your cooking adventures with friends and family. Every conversation about this remarkable fruit helps build awareness of sustainable, climate-resilient foods that could reshape our agricultural future.

source https://harvestsavvy.com/breadfruit/

No comments:

Post a Comment