Picture this: It’s January, snow blankets the ground, and you’re walking down steps into your backyard, opening a door to a warm sanctuary filled with fresh lettuce, vibrant herbs, and ripening tomatoes. No heating bill. Just the earth doing what it does best—keeping things stable.

This is the promise of an underground greenhouse, also known as a walipini (Aymara for “place of warmth”).

These structures have been helping farmers defy their local climates for decades, and they might be exactly what you need to grow fresh food when your neighbors are ordering from the grocery store.

What Is an Underground Greenhouse and How Does It Work?

An underground greenhouse flips conventional thinking on its head. Instead of sitting on top of the ground with four transparent walls, it’s partially or fully sunken into the earth—typically 3 to 8 feet deep.

Only the roof allows light to enter, while the surrounding soil acts as both insulator and battery.

The Physics Behind the Magic

About 4 to 6 feet below the surface, soil maintains a remarkably consistent temperature year-round—usually between 50 and 60°F, whether it’s scorching summer or freezing winter above.

During sunny days, light streams through the angled roof, warming the interior. The earth, stone walls, or water barrels absorb this excess heat. When the sun sets, that stored warmth slowly radiates back into your growing space through three natural processes:

- Radiation (direct sunlight warming surfaces)

- Conduction (heat moving through materials)

- And convection (warm air rising and circulating).

It’s a beautifully simple system that requires no fossil fuels.

From Bolivian Mountains to Your Backyard

The modern walipini was born in 2002 when Benson Agriculture and Food Institute volunteers traveled to La Paz, Bolivia, to help high-altitude farmers grow food year-round.

Their design—a rectangular pit covered with plastic sheeting—was cheap, effective, and life-changing.

But the concept has deeper roots: Victorian British gardeners used “pineapple pits,” Russian farmers experimented with underground structures, and Chinese farmers have long used earth-bermed greenhouses for winter vegetables.

What makes today’s designs accessible is the availability of affordable glazing materials and better engineering knowledge.

The Real Benefits and Honest Limitations

Why Underground Greenhouses Excel

Temperature stability is the game-changer. While traditional greenhouses can swing 40-50 degrees between day and night, underground structures maintain much narrower fluctuations—critical for consistent plant growth.

This translates to energy savings of 70-90% compared to heated above-ground greenhouses. Many growers in zones 6-7 report using zero supplemental heat, relying entirely on earth’s warmth and captured solar energy.

The structure also provides exceptional protection from hailstorms, high winds, and heavy snow loads. Being underground creates a natural barrier against foraging animals and many pests.

Depending on your climate and design, you can extend your growing season by 2-3 months or achieve true year-round production.

The Limitations You Must Understand

Geography matters immensely

In far northern regions (zones 3-4 or above 45° north latitude), winter sun hangs so low that in a deep pit, sunlight simply can’t reach the bottom growing area. You’re left with a shaded hole.

Solutions include building shallower (3-4 feet maximum), incorporating a tall south-facing glass wall, or accepting that supplemental LED lighting will be necessary.

Water management is non-negotiable

Without excellent drainage, you’re building an underground pool. Areas with high water tables (less than 13 feet deep), heavy rainfall, or clay soil require extensive French drain systems, waterproofing, and possibly sump pumps.

This single factor causes more failures than anything else.

Initial construction demands significant effort

Excavating hundreds of cubic feet of soil, building retaining walls, installing drainage, and constructing a properly-angled roof is serious work.

While enthusiasts claim $300 builds using salvaged materials and sweat equity, realistic budgets run $3,000-8,000 for properly engineered structures, with elaborate designs reaching $15,000-20,000.

You’re trading some light for temperature stability

Your growing area receives light only from above, not from all sides. This requires careful crop selection and possibly supplemental lighting in winter.

Ventilation is also trickier—poor airflow can lead to excessive humidity, mold, and even dangerous gas buildup (radon or carbon dioxide). You must design adequate venting from the start.

Is This Right for You? A Decision Framework

Before grabbing a shovel, assess your situation honestly.

- You’re an ideal candidate if:

You live in zones 5-8 with cold winters but decent winter sun, have well-draining soil with a water table at least 13 feet deep, own your property long-term, primarily want to grow cold-hardy crops (greens, herbs, roots), and have access to excavation equipment or strong determination.

- Proceed cautiously if:

You’re in zones 3-4, live in extremely wet climates, have clay-heavy soil, rent your property, want to grow heat-loving crops year-round in very cold climates, or have a tight budget with no cushion for surprises.

- Seek alternatives if:

You’re in zones 9-11 (cooling matters more), have high water tables or flood-prone land, have extremely shaded property, live at very high latitudes with minimal winter sun, want maximum growing space for large fruiting crops, or prefer mobility over permanent structures.

Choosing Your Design Approach

- The Traditional Walipini (Full Pit)

A rectangular hole 6-8 feet deep with earthen walls and an angled roof. Maximum temperature stability and lowest heating costs, but requires most excavation, has trickiest drainage, and most restricted light. Best for stable, dry soils in moderate climates.

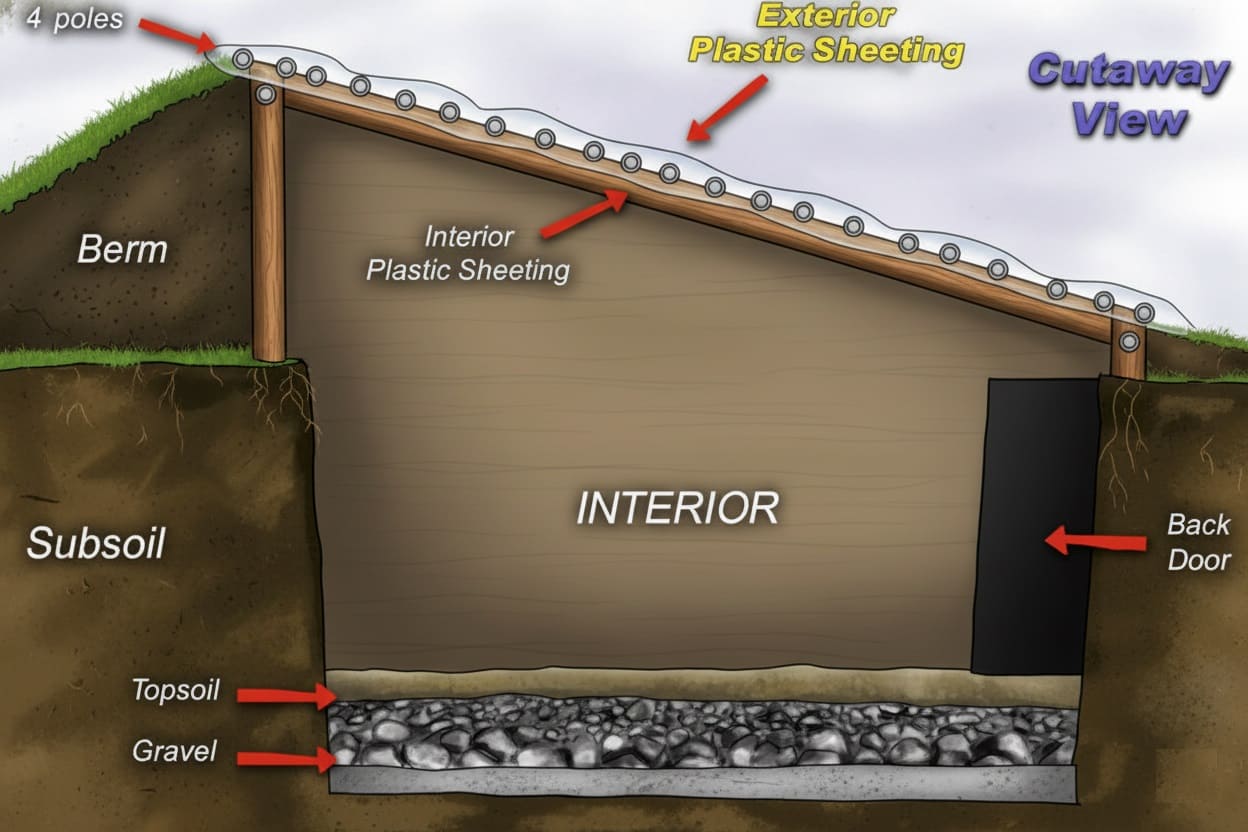

- The Earth-Sheltered Greenhouse (Hybrid)

Mike Oehler’s design digs down 3-4 feet with wooden posts supporting walls that extend above ground. The north side is heavily bermed while the south side features maximum glazing.

Better for northern latitudes, provides more light, easier construction and ventilation, but loses more heat than full pits.

- The Chinese-Style Greenhouse

Barely sunken (1-2 feet) with a heavily insulated north wall, maximum south-facing glazing, and removable insulating blankets covering the greenhouse at night. Offers maximum growing space with good sun, but requires daily labor to manage blankets.

Building Your Underground Greenhouse: The Complete Process

Phase 1: Site Analysis and Planning

Evaluate your land thoroughly.

Contact local well drillers to determine water table depth—you need at least 13 feet. Test drainage by digging a 2-foot hole, filling it with water, and timing how fast it drains (should empty within 24 hours).

Observe winter sun patterns for at least a month if possible—you need 6+ hours of direct southern exposure.

Call 811 to mark underground utilities. Check local building codes; some jurisdictions classify underground structures differently than surface greenhouses.

Critical design calculations:

Your roof angle should be perpendicular to the sun’s rays on the winter solstice (typically 39-40° from horizontal in mid-latitudes). Face the long dimension east-west with maximum glazing on the south side (north in Southern Hemisphere). For a starter greenhouse:

- Length: 12-16 feet (east-west)

- Width: 8-10 feet (north-south)

- Depth: 3-4 feet below grade (shallower in northern zones)

- North wall height: 8 feet above floor

- South wall height: 6 feet above floor

Phase 2: Excavation and Structural Support

Mark your perimeter with stakes and string, adding 2 feet on all sides for working room. If hiring a backhoe (recommended), excavate to your desired depth plus 2 feet for drainage layers. Critical: slope walls at 6-8 inches back from bottom to top to prevent collapse.

Here’s what many builders miss—managing soil pressure. Earth exerts tremendous lateral force on underground walls. Your options:

- Rammed earth: Traditional method using a 6-8 inch backward slope. Works well in sandy or gravelly soil but risky in clay.

- Cob or earthbag construction: Better for clay-rich soils. Stack and compact earth-filled bags or build with clay-straw mixture.

- Timber shoring: Install 6×6 posts every 4-6 feet with horizontal planks behind them. Backfill with gravel between planks and earth for drainage.

- Concrete block or poured concrete: Most permanent but also most expensive. Essential if water intrusion is likely.

Along walkways, dig an additional 12-18 inches deeper than growing beds—this “cold sink” allows the coldest air to settle below plant level rather than around your crops.

Phase 3: The Foundation—Getting Drainage Right

This determines success or failure. Line the entire pit with commercial-grade landscape fabric (not cheap stuff). Install your drainage system:

- Bottom layer: 12 inches of large gravel or fist-sized stones

- Drainage pipes: Perforated 4-inch pipes running the length, sloped 1 inch per 10 feet toward collection sumps

- Middle layer: 4-6 inches of medium gravel

- Fabric barrier: Another layer of landscape fabric to prevent soil migration

- Growing medium: 8-12 inches of quality topsoil mixed with compost

Create drainage sumps in opposite corners—simply extend the pit 2 feet deeper in a 2×2 area, fill with gravel, and install removable lids for access. If you’re in a wet climate, add manual pumps or battery-powered automatic pumps that activate when water rises.

External drainage: Create a shallow (6-inch) gravel-filled trench around the greenhouse perimeter, sloped away from the structure. Install gutters on the roof to capture and divert water, not let it pour onto your bermed walls.

Phase 4: Wall Construction and Berming

For timber-supported walls, install 6×6 treated posts buried 3 feet deep in concrete or compacted gravel. Critical: wrap buried portions in 6-mil plastic to prevent rot. Connect posts with horizontal 2×8 or 2×10 boards, creating a sturdy frame.

Behind this, you can leave exposed earth (if stable), install additional planks, or attach rigid foam insulation board in very cold climates.

Berm the north wall by piling excavated soil to create a slope extending 4-6 feet from the wall and rising above it. This provides insulation and supports your roof angle. Pack firmly and cover with landscape fabric or plant with low-growing groundcover to prevent erosion.

In dry climates, you might line this berm with plastic sheeting to direct water away, though this reduces the thermal benefit slightly.

Phase 5: Roof Engineering

This is where many DIY builds fall short. Your roof must support snow loads, manage condensation, prevent heat loss, and capture maximum sunlight.

Frame construction: Install rafters from north wall to south wall at your calculated angle (typically 39-40°), spacing them 24 inches on center.

Use 2x8s minimum for spans over 10 feet. Add cross-bracing and ensure the frame can handle expected snow loads—check your local building codes for requirements.

Glazing options compared:

- Twin-wall polycarbonate (8-10mm): Best balance of insulation (R-1.6 to R-2), light transmission (80-82%), and durability (10-15 years). Costs $2-3 per square foot. Easy to work with and relatively impact-resistant.

- Triple-wall polycarbonate (16mm): Better insulation (R-2.8) but reduced light transmission (75%). Worth it in zones 5 and colder. Costs $3-5 per square foot.

- Double-layer greenhouse plastic: Cheapest option ($0.30-0.50 per square foot) with surprisingly good R-value when inflated (R-1.7). Requires replacement every 4-5 years. Install one layer on top of rafters, another underneath, creating a 4-inch air gap.

- Glass: Beautiful and permanent but expensive ($8-15 per square foot), heavy (requires stronger framing), and provides poor insulation unless double-pane. Only consider for attached greenhouses where appearance matters.

Condensation control—the overlooked problem:

As warm, moist air hits cold glazing, condensation forms. If not managed, it drips on plants, promoting disease. Solutions include:

- Slope glazing at least 30° so condensation runs down, not drips

- Install a gutter at the bottom edge of glazing to collect runoff

- Channel this water into your irrigation system or away from plants

- Ensure proper ventilation to reduce humidity (target 50-70%)

Phase 6: Ventilation Systems That Actually Work

Poor ventilation ruins more underground greenhouses than almost anything else. You need air exchange for cooling, humidity control, and safety (preventing CO₂ and radon buildup).

Minimum requirements: For every 100 square feet of floor space, you need one of these combinations:

- Two automatic vent openers (install one at the peak of the north wall, one low on the south wall for cross-ventilation)

- One thermostat-controlled exhaust fan (100-150 CFM) at the peak with passive intake vents low on the opposite wall

- Manual vent panels you commit to opening daily

Why both high and low vents matter: Hot air rises and exits through the peak vent. This creates negative pressure that pulls fresh air in through lower vents, creating circulation. Single vents don’t create this flow.

For automatic temperature control, install a simple thermostat that opens peak vents at 75°F and activates exhaust fans at 85°F. Even in winter, sunny days will trigger these—you want that circulation.

Phase 7: Interior Setup for Maximum Production

- Thermal mass optimization:

Place 55-gallon drums filled with water along the north wall, spacing them 2-3 feet apart. Paint them flat black for maximum heat absorption.

On a sunny 50°F winter day, these can absorb enough heat to keep your greenhouse 15-20 degrees warmer than outside overnight. In summer, they provide cooling thermal mass. Use the water for irrigation as needed—replace monthly to prevent algae.

- Growing bed arrangement:

In a 10-foot-wide greenhouse, create two 3-foot-wide beds running the length, with a 3-4 foot central walkway (which sits lower as your cold sink).

This arrangement allows comfortable access to all plants. Install raised beds (10-12 inches high) using untreated lumber or concrete blocks if you want easier working height.

- Install a basic irrigation system:

Even a simple drip line connected to rain barrels or a hose makes life easier. Underground greenhouses have higher humidity than outdoor gardens but still need consistent watering.

A timer-controlled drip system ($50-100) pays for itself in time saved and better plant growth.

- Lighting considerations:

If you’re in zones 5 or colder, budget for supplemental LED grow lights. You need approximately 400-600 foot-candles for leafy greens, 800-1000 for fruiting crops.

Hang full-spectrum LED shop lights 6-12 inches above plants on adjustable chains. Set them on a timer for 12-14 hours in winter months when natural light dips below 6 hours daily.

What to Grow: Seasonal Strategies for Maximum Success

Winter: Proving Your Design (December-February)

Focus on crops that thrive in lower light and cooler temperatures. Keep nighttime temps at 37-45°F for optimal growth of cold-hardy crops—any warmer wastes stored heat, any colder stresses plants unnecessarily.

- Star performers:

Lettuce varieties (Black-Seeded Simpson, Winter Density), spinach, arugula, kale (Lacinato, Red Russian), Asian greens (bok choy, mizuna), herbs (parsley, cilantro, chives), and root vegetables (carrots, radishes, turnips).

These crops actually prefer the cooler conditions and will produce steadily.

- Technique matters:

Use succession planting—sow new lettuce every 2 weeks for continuous harvest. Cut leaves rather than pulling whole plants for extended production. Mulch beds lightly with straw to conserve moisture and add minor insulation.

On extremely cold nights (below 10°F outside), drape frost blankets (not plastic) over sensitive crops. The thermal mass should handle most cold snaps, but this insurance costs little and prevents heartbreak.

Spring: Maximum Productivity (March-May)

Your greenhouse becomes a powerhouse for starting warm-season crops while still harvesting cool-season ones. This is when you’ll appreciate the structure most—starting tomatoes in February while snow still covers the ground.

Start tomato, pepper, and eggplant seedlings 6-8 weeks before your last outdoor frost. Use quality seed-starting mix in 4-inch pots. Keep them near the south wall where light is strongest.

Once true leaves form, transplant to 1-gallon pots and maintain them in the greenhouse until outdoor temperatures stabilize.

Continue harvesting winter greens through April, then clear beds for warm-season crops if you plan to summer them indoors. Start cucumber and squash seedlings 3-4 weeks before outdoor transplanting.

- Critical transition:

Harden off seedlings before outdoor transplanting by gradually exposing them to outside conditions over 7-10 days. Start with 1-2 hours of outdoor time, increasing daily. Shocking tender greenhouse-grown plants with full sun and wind stresses them severely.

Summer: Managing Heat (June-August)

Your focus shifts from heating to cooling. The earth’s thermal mass that warmed you in winter now keeps things cooler than outside—but you still need active management.

In zones 6-7, you can successfully grow tomatoes, peppers, basil, and eggplant if you have excellent ventilation. Keep all vents open 24/7. Monitor afternoon temperatures—if consistently exceeding 95°F, add 30-40% shade cloth over the south-facing roof.

In zones 8-9 or if your greenhouse regularly exceeds 100°F despite ventilation, switch to shade-tolerant summer crops: lettuce varieties bred for heat (Jericho, Nevada), spinach, chard, and herbs like mint and parsley.

Your underground structure will actually keep these cooler than they’d be in outdoor gardens.

- Evaporative cooling:

Hang wet burlap over intake vents. As air passes through the damp fabric, evaporation cools it by 10-15 degrees. Mist the burlap daily or set up a drip system to keep it damp.

Learn about Desert Gardening for Beginners: Growing Food & Plants in Extreme Heat

Learn about Desert Gardening for Beginners: Growing Food & Plants in Extreme Heat

Fall: Reset and Succession (September-November)

Fall is your opportunity to reset for winter production. In late August/September, start winter salad green varieties. Plant garlic cloves 4 inches deep in October for spring harvest—they’ll develop roots through winter and shoot up in early spring.

Succession plant herbs like cilantro (which bolts in summer heat) and parsley. Sow brassicas (broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage) in September for harvest through December and January.

- Transition tasks:

Clean thoroughly before winter—remove old mulch, scrub walkways, sanitize pots and tools with diluted bleach solution.

Check all seals, test ventilation systems, repair any glazing damage. Organize and pot up perennial herbs from outdoor gardens to overwinter (rosemary, oregano, thyme).

Advanced Optimization: Taking Performance to the Next Level

Humidity Management

Underground greenhouses naturally run 60-80% humidity—higher than most outdoor gardens. While this benefits many crops, excessive humidity (above 80%) encourages fungal diseases. Monitor with a hygrometer and maintain 55-70% as your target range.

- Reduce excess humidity by:

Increasing ventilation, watering in the morning rather than evening (allows daytime evaporation), spacing plants adequately for airflow, using drip irrigation rather than overhead watering, and removing dead plant material promptly.

- Increase insufficient humidity (<40%) by:

Placing open water trays between plants, misting in the morning, reducing ventilation slightly, and mulching beds to slow evaporation.

Soil Health in Enclosed Systems

Unlike outdoor gardens where rain leaches excess salts and provides fresh nutrients, underground greenhouse soil can develop imbalances over time.

Maintain soil health by:

- Testing pH and nutrient levels every 3 months (most crops prefer 6.0-6.8 pH)

- Adding compost or well-rotted manure before each crop planting (2-3 inches worked into top 6 inches)

- Rotating crop families season-to-season (don’t plant tomatoes where peppers just grew)

- Occasionally flooding beds with water to leach accumulated salts (then ensure good drainage)

- Adding organic matter continuously to maintain soil structure

Here’s How to Add Nitrogen to Soil: 18 Quick Fixes + Long-Term Solutions

Here’s How to Add Nitrogen to Soil: 18 Quick Fixes + Long-Term Solutions

Pest Management in Protected Environments

The good news: Many outdoor pests never find your underground greenhouse. The bad news: pests that do get in find paradise—stable temperatures, no rain to wash them off, no predators.

Common problems and solutions:

- Aphids: Most common pest. Spray with insecticidal soap or introduce beneficial insects (ladybugs, lacewings). Yellow sticky traps catch adults.

- Whiteflies: Use yellow sticky traps heavily and spray with neem oil. These multiply rapidly in warm conditions.

- Fungus gnats: Indicate overwatering. Let soil dry slightly between waterings. Apply Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (BTI) if severe.

- Spider mites: Thrive in hot, dry conditions. Increase humidity, spray with water to knock them off, use insecticidal soap for infestations.

Prevention trumps treatment:

Inspect all plants before bringing them into the greenhouse. Maintain good air circulation. Don’t overwater. Remove dead plant material promptly. Keep a diary of pest issues to identify patterns.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: Greenhouse stays too cold at night (below 35°F) even though outside temps are only 20°F.

- Diagnosis: Insufficient thermal mass or heat loss through glazing.

- Solutions: Add more water barrels along north wall. Verify glazing is properly sealed—use infrared thermometer to find cold spots. Consider adding thermal blankets to drape over glazing on coldest nights. If using single-layer plastic, upgrade to double-layer or polycarbonate.

Problem: Excessive condensation dripping on plants.

- Diagnosis: High humidity meeting cold glazing surface, poor ventilation.

- Solutions: Increase air circulation even in winter—crack vents open midday. Ensure glazing slopes adequately (minimum 30°). Install collection gutters at lower glazing edge. Water in morning, not evening. Reduce total water use.

Problem: Plants wilting despite moist soil.

- Diagnosis: Root rot from overwatering or poor drainage.

- Solutions: Check drainage system—are pipes clogged? Is water accumulating in low spots? Reduce watering frequency dramatically. Pull affected plants, improve drainage, let soil dry out substantially before replanting.

Problem: Everything grows slowly with pale, weak growth.

- Diagnosis: Insufficient light, especially in winter.

- Solutions: Install supplemental LED grow lights on 12-14 hour timers. Clean glazing—dirt and dust can reduce light transmission 30%. Verify trees or structures aren’t shading greenhouse during peak sun hours. Consider reflective white paint or Mylar on north wall to bounce light onto plants.

Problem: Temperature spikes to 100°F+ on sunny spring/fall days.

- Diagnosis: Insufficient ventilation.

- Solutions: Add more automatic vent openers or larger exhaust fans. Verify vents are actually opening (automatic openers can fail). Install shade cloth temporarily. Consider adding evaporative cooling system.

Real-World Performance: What to Expect

Let’s set realistic expectations. A well-designed underground greenhouse in zone 6 (where outdoor growing season runs April-October) can extend your season to February-November—roughly 3 additional months.

You’ll harvest cold-hardy greens through winter, start warm-season crops 6-8 weeks earlier, and continue fall crops 6-8 weeks later than outdoor gardens.

Your energy costs will be minimal—perhaps $50-100 annually for supplemental heat during extreme cold snaps, plus electricity for ventilation fans ($20-40/year). Compare this to heated greenhouses where $500-2000 annually is common for similar-sized structures.

Production-wise, a 10×12 foot underground greenhouse (120 square feet) can produce:

- 50-75 lbs of salad greens annually with succession planting

- 30-40 lbs of herbs

- 20-30 lbs of tomatoes if grown May-October

- Dozens of seedlings for outdoor transplanting

- Overwintered perennials and tender plants

Your ROI depends on your build costs and what you value. If you spent $5,000 building it and save $800 annually in produce (realistic for an active grower), you’ll break even in 6-7 years, then profit for decades.

But many builders value food security, the joy of winter gardening, and self-sufficiency more than dollars.

Taking the First Step

Building an underground greenhouse isn’t a weekend project—it’s a commitment requiring weeks of labor and thousands of dollars.

But the rewards compound year after year: food security, dramatically lower operating costs than traditional greenhouses, and the deep satisfaction of harvesting basil when snow covers the ground.

If you’re uncertain, start with a simple growing pit: a 3-foot-deep hole covered with an old window or sheet of polycarbonate.

It costs under $100, teaches you the principles, and produces real food. After a season, you’ll understand whether you want to commit to a full structure.

Understand that your first season is tuition in the school of underground growing. You’ll make mistakes, discover your structure’s quirks, lose crops to unexpected issues.

That’s not failure—that’s learning. By your second year, you’ll confidently harvest tomatoes in October and plant lettuce in February while neighbors marvel at your year-round green thumb.

The earth has been regulating temperatures since long before greenhouses existed. You’re simply learning to work with that ancient wisdom. Now make that first shovel of dirt count.

source https://harvestsavvy.com/underground-greenhouse/

No comments:

Post a Comment