Have you noticed fewer monarch butterflies gracing your garden lately? You’re not imagining it. Over the past two decades, monarch populations have plummeted by as much as 90 percent, with Western monarchs faring even worse.

The culprits? Habitat loss, pesticides, and climate change have conspired to threaten one of North America’s most iconic insects.

But here’s the good news: you hold incredible power to reverse this trend, and it starts with a single plant. Milkweed—the monarch butterfly’s lifeline—is surprisingly easy to grow, even for gardening beginners.

By the end of this guide, you’ll have everything you need to transform your yard into a thriving monarch sanctuary, complete with practical tips that work in real gardens, not just in theory.

Why Milkweed Is Non-Negotiable for Monarchs

Milkweed (genus Asclepias) serves two irreplaceable functions. Adult monarchs lay their eggs exclusively on milkweed leaves.

When those eggs hatch, the tiny caterpillars feed on nothing but milkweed foliage until they’re ready to form their chrysalis—eating 20 or more leaves per caterpillar.

The relationship goes deeper than food. Milkweed contains cardiac glycosides—natural compounds that make monarch caterpillars and adult butterflies toxic to most predators. This chemical protection, acquired by eating milkweed, is crucial for their survival.

The benefits extend beyond monarchs. Milkweed flowers attract diverse pollinators including native bees, honeybees, hummingbirds, and numerous butterfly species.

The unique flower structure produces abundant nectar and facilitates effective pollination. You’re not just helping one species—you’re supporting an entire ecosystem.

The crisis stems from habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change decimating milkweed populations across North America.

Agricultural expansion has been particularly devastating, eliminating millions of acres of milkweed-rich meadows and field edges that once sustained monarch migrations.

Choosing the Right Milkweed: Native Species Matter

The genus Asclepias contains over 140 species, but only about 25 serve as important monarch hosts. Of these, even fewer thrive in home gardens. Here’s your first critical decision point.

The Golden Rule: Plant Native to Your Region

Native milkweeds naturally occur in your area and have evolved alongside local monarchs and ecosystems.

They’re adapted to your climate, require minimal maintenance once established, and support the entire food web—not just butterflies, but specialized insects like milkweed beetles and tussock moths that have coevolved with these plants.

Top Native Milkweed Species by Region:

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Hardy in zones 3-9, this robust species grows throughout the eastern U.S. and Canada, west to the Rocky Mountains.

Reaching 3-5 feet tall, it produces fragrant pink-purple flower clusters from June through August. This is the milkweed you’ll see growing wild along roadsides and in meadows.

The catch? Common milkweed spreads aggressively through underground rhizomes and prolific seed production.

Think of it as an enthusiastic guest who invites all their friends—wonderful for large spaces, meadows, and naturalized areas, but overwhelming in a tidy perennial border.

If you choose this species, plant it where it has room to roam or be prepared to manage its spread.

Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

Despite the name, swamp milkweed (zones 3-9) tolerates average garden soil beautifully—it just handles moisture better than other species.

Growing 3-5 feet tall, it produces vanilla-scented mauve, pink, or white flowers from midsummer through fall, blooming longer than most milkweed species.

This is your best choice for traditional garden settings. Unlike common milkweed, it forms well-behaved clumps rather than spreading aggressively. It works perfectly in perennial borders, rain gardens, and even containers.

Cultivars like ‘Cinderella’ (mauve-pink), ‘Ice Ballet’ (creamy white), and ‘Soulmate’ (fragrant pink) offer color variations while maintaining the clumping habit.

Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

This shorter species (1-2 feet) thrives in zones 3-9 throughout the eastern U.S. and as far west as Texas and Minnesota.

The brilliant orange, yellow, or red flowers bloom from late spring through fall, creating stunning displays that work beautifully in borders, rock gardens, and containers.

Butterfly weed develops a deep taproot that makes it exceptionally drought-tolerant once established but also means it strongly resists transplanting. Plant it where you want it to stay.

Unlike other milkweeds, the sap is clear rather than milky. The ‘Gay Butterflies’ seed mix offers color diversity including reds and yellows alongside traditional orange.

Showy Milkweed (Asclepias speciosa)

Native to the western U.S. from the Great Plains to California (zones 3-9), this 1-3 foot tall species produces rose-purple and pink flowers throughout summer.

It’s the primary monarch food source for western populations and handles arid conditions better than eastern species.

Showy milkweed spreads moderately through rhizomes but less aggressively than common milkweed. It’s ideal for prairie restorations, xeriscaping, and gardens in dry western climates.

Regional Considerations

For the Southeast, consider sandhill milkweed (A. humistrata), which emerges and blooms in May exactly when spring monarch migration peaks in this region.

Western gardeners should explore narrow-leaf milkweed (A. fascicularis) or desert milkweed (A. erosa) for hot, dry climates.

In the Southwest, several native species including Arizona milkweed (A. angustifolia) and rush milkweed (A. subulata) handle extreme heat.

The Tropical Milkweed Question

You’ll frequently see tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) at garden centers. It’s gorgeous—vibrant red and orange flowers, rapid growth, prolific blooming—and it’s not native to the continental United States.

In warm climates (zones 8-11) where tropical milkweed doesn’t die back in winter, it disrupts monarch migration patterns. Butterflies that should continue south to overwintering grounds in Mexico may instead linger and breed.

This sounds beneficial but creates two serious problems: higher infection rates from OE (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha), a debilitating protozoan parasite that builds up on evergreen milkweed, and increased vulnerability to winter cold snaps.

If you’re in zones 8-11 and already have tropical milkweed, cut it back to a few inches in late fall and winter. This removes the temptation for monarchs to breed out of season and reduces parasite buildup.

Better still, gradually replace it with native species that naturally go dormant and support your local ecosystem.

Seeds vs. Transplants: Choosing Your Path

Starting from Transplants

Buying young plants from reputable native plant nurseries offers faster results and higher success rates for beginners.

The critical timing is spring after your last frost date, or fall at least 6-8 weeks before the first frost. Fall planting allows roots to establish over winter, giving you a head start for the following season.

When your plants arrive in spring, don’t panic if they look completely dead—just bare roots and a woody crown with no leaves. Milkweed is notoriously late to break dormancy, sometimes not showing signs of life until late May or even June.

The plants are focusing energy on developing deep root systems underground. Resist the urge to overwater dormant plants; this is the number one cause of failure.

Proper Transplanting Technique:

Before planting, score or gently loosen circling roots to encourage outward growth. Dig a hole twice as wide but only as deep as the root ball—don’t bury the crown any deeper than it was in the pot.

After planting, water thoroughly, then let the soil dry out considerably before watering again.

For the first growing season, water deeply once or twice weekly to encourage deep root development, then taper off as plants establish. By the second year, most species need supplemental water only during extended droughts.

Starting from Seed

Growing from seed costs less, produces more plants, and gives you access to uncommon species. The trade-off is patience and understanding cold stratification—the process that makes or breaks seed germination.

Understanding Cold Stratification

Most native plants have evolved seed dormancy mechanisms that prevent germination at the wrong time. In nature, milkweed seeds fall to the ground in autumn and lie dormant through winter.

Freeze-thaw cycles and cold moisture gradually soften the seed coat and break down chemical germination inhibitors.

When spring arrives with rising temperatures, seeds “know” it’s safe to sprout.

- Method 1: Fall Sowing (Easiest)

In October or November after the first frost, choose your planting area and clear competing vegetation. Rake the soil surface to loosen it, then scatter seeds directly on top—they need light to germinate, so barely cover them with 1/4 inch of soil.

Gently press seeds into contact with soil using your hand or the back of a rake. Walk away and let winter work its magic. Come spring, seeds will germinate naturally when conditions are right, typically yielding excellent germination rates.

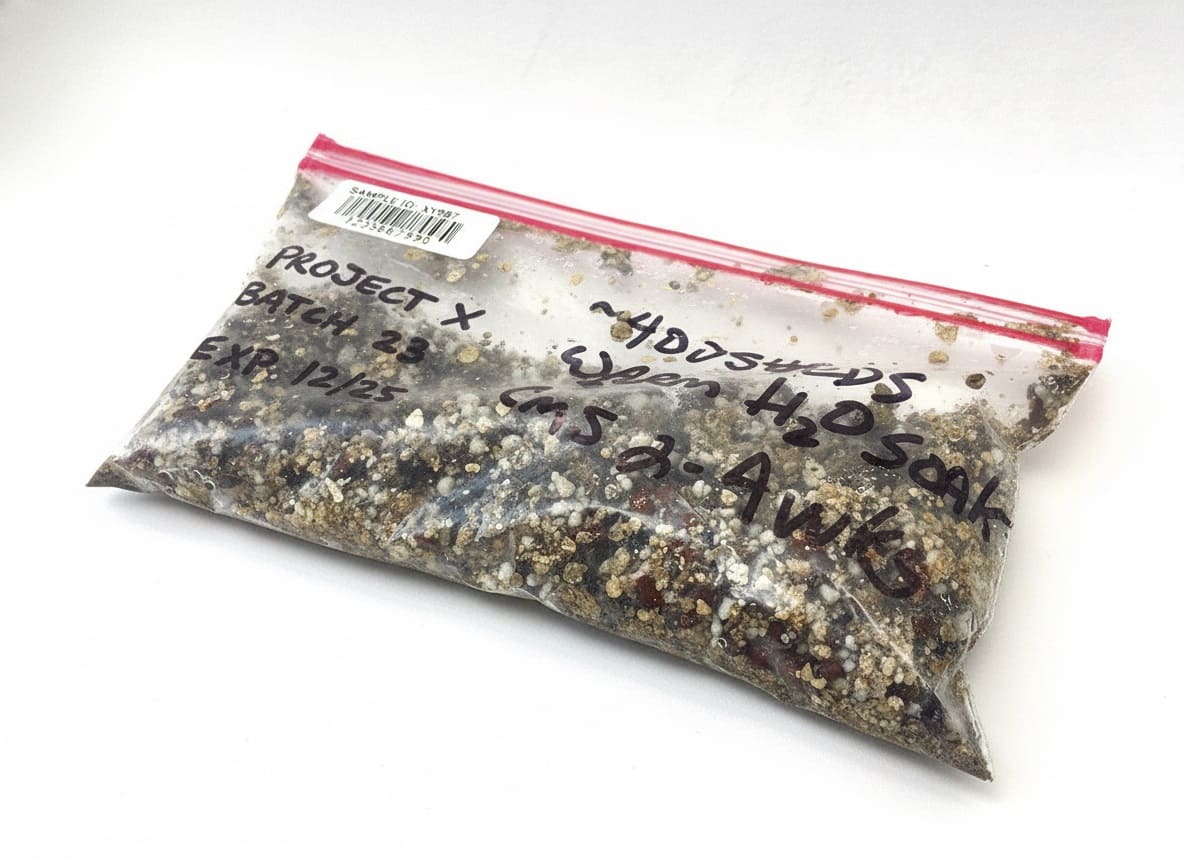

- Method 2: Refrigerator Stratification (Spring Planting)

For spring planting, cold-stratify seeds in your refrigerator for 30-60 days (longer is generally better, up to 3 months).

Place seeds between damp—not soaking wet—paper towels or mix with moist sand in a sealed plastic bag. Store in the crisper drawer where they won’t be disturbed.

Check weekly to ensure the medium stays moist. After 30+ days, check every few days for tiny white roots emerging from seeds. Once roots appear, plant immediately to avoid damage.

Starting Seeds Indoors

Use biodegradable peat pots or newspaper pots with drainage holes—milkweed’s sensitive taproot makes transplanting tricky, so plantable pots minimize shock. Fill pots three-quarters full with seed-starting mix and plant 1-2 seeds per pot about 1/4 inch deep.

Place pots in a sunny south-facing window or under grow lights positioned 6 inches above seedlings. Maintain temperatures around 70-75°F. Properly stratified seeds typically germinate within 7-15 days, though some may take several weeks.

If seedlings become leggy (tall and spindly), they need more light—move them closer to the light source or increase hours of exposure. A small fan creating gentle air circulation helps strengthen stems.

Transplant outdoors when seedlings reach 3-4 inches tall with multiple sets of true leaves, planting the entire peat pot directly in the ground. Cut the bottom off the pot just before planting so roots can spread freely while the pot sides prevent transplant shock.

Creating the Perfect Milkweed Home

Location Requirements

Milkweed thrives in full sun—provide at least 6-8 hours of direct sunlight daily. In the wild, milkweed grows in open fields, along roadsides, in meadows, and at forest edges. Your garden equivalent is the sunniest spot available, away from building and tree shade.

Space plants 18-24 inches apart for butterfly weed and common milkweed, or 30-36 inches for swamp milkweed, which forms wider clumps.

Plant in groups or patches of at least six plants rather than scattering individuals throughout the garden. Monarchs are more likely to find and use visible clusters than isolated plants.

Here’s a design strategy: place taller milkweed species at the back or center of beds, then plant low-growing perennials or groundcovers in front.

As caterpillars munch lower leaves and plants develop that characteristically eaten look, shorter plants camouflage the damage while still allowing butterfly access to flowers.

Soil and Drainage

One of milkweed’s best features is its tolerance for poor soil. Most species thrive in average, unimproved soil and actually perform better without heavy amendment.

Common milkweed and butterfly weed prefer well-drained, average to dry conditions and excel in poor, rocky soil. Once established, they’re remarkably drought-tolerant.

Swamp milkweed tolerates heavier, moister soil but still needs decent drainage—perfect for rain gardens or naturally damp areas.

If you have heavy clay that puddles after rain, consider building a raised bed or mounding soil for better drainage (except for swamp milkweed). Sandy or rocky soil is ideal as-is for most species. Soil pH between 4.8-7.2 works well.

Container Growing

Growing milkweed in containers works well for apartment dwellers or those wanting strategic placement on decks and patios.

Choose containers at least 14-16 inches deep and wide to accommodate the taproot, with excellent drainage holes. Use quality potting mix—not garden soil—and remember containers dry faster than beds, often requiring daily watering in hot weather.

Container plants benefit from monthly feeding during the growing season with balanced, water-soluble fertilizer diluted to half strength.

Critical First-Year Care

During the first growing season, water deeply once or twice weekly to help establish strong root systems, then gradually reduce frequency.

The soil should dry out between waterings—check by inserting your finger 2 inches deep. If it feels moist, wait. By the second year, most species rarely need supplemental water except during prolonged drought.

This first-year patience is crucial. Your newly planted milkweed may grow slowly and rarely blooms—that’s normal. The plant is investing energy in developing extensive roots.

Second-year plants look more robust. Third-year plants reach mature size and flower reliably. This delayed gratification requires faith, but established milkweed becomes increasingly self-sufficient and productive.

Ongoing Care: The Less-is-More Philosophy

Watering Mature Plants

Once established after the first year, most milkweed species need water only during extended dry spells. The exception is swamp milkweed, which appreciates consistent moisture—though “moist” doesn’t mean “soggy.”

Overwatering causes root rot and fungal problems. Let the top inch of soil dry out between waterings. When you do water, water deeply to encourage deep root growth rather than shallow, frequent watering that promotes surface roots.

Fertilizing (Probably Not Needed)

Native milkweeds evolved in prairies and meadows with lean soil. They don’t need or expect fertilizer. Excessive nutrients can promote lush, weak growth that’s more susceptible to pests and diseases.

If you feel you must fertilize, limit it to a single light application of compost in spring. Container-grown plants are the exception, benefiting from monthly feeding at half strength during the growing season.

Mulching Considerations

Most milkweed doesn’t need mulch. Heavy bark mulch can hold too much moisture against the crown and promote rot.

If you live in an extremely hot climate or want weed suppression, use a light layer of pine needles or straw—never pile mulch against the plant crown.

Pruning and Deadheading

Deadhead spent flower clusters by cutting just above the next set of leaves to encourage a second flush of blooms, extending the nectar availability for monarchs and other pollinators. This is optional—you’re trading potential seed production for more flowers.

In late fall or early spring, cut dead stems back to 2-3 inches above ground. Some gardeners leave stems standing through winter to provide habitat for overwintering beneficial insects, then cut them back in early spring before new growth emerges.

Related posts:

- When and How to Deadhead Cosmos for Continuous Blooms

- How and Why to Deadhead Daylilies for Boosting Blooms

- How to Deadhead Salvia for Healthier Blooms And Extend Your Garden’s Beauty

When to Worry About Damage

Seeing holes in your milkweed leaves isn’t a problem—it’s a success metric. Each monarch caterpillar eats 20+ leaves before pupating. If plants are completely defoliated, they’ll typically resprout fresh leaves in a few weeks.

This is why planting multiple milkweed plants is essential—you need enough foliage to feed caterpillars while maintaining plant vigor.

Recognizing and Managing Problems

Aphids (Usually Harmless)

Oleander aphids—also called milkweed aphids—are bright yellow-orange insects that cluster on stems, leaves, and flower buds. They look alarming in large numbers but rarely cause serious harm.

Natural predators like ladybugs, lacewings, and hoverflies usually keep populations in check.

If aphid populations explode, spray them off with a strong stream of water, taking care to avoid monarch eggs (tiny white dots on leaf undersides) or caterpillars.

Never use insecticidal soap or any pesticide—it will kill monarch eggs and caterpillars along with aphids.

Milkweed Bugs (Generally Beneficial)

Large milkweed bugs (orange and black) and small milkweed bugs (black with red markings) feed on seeds and seed pods but don’t harm leaves or flowers.

They’re part of the native milkweed ecosystem and generally aren’t worth removing unless populations are extremely high. If you want to collect seeds, harvest pods before bugs damage them.

Milkweed Tussock Moth Caterpillars

These hairy orange, black, and white caterpillars also feed on milkweed. They’re native, won’t harm monarchs, and deserve their place in your garden. They can occasionally defoliate plants, but milkweed typically recovers.

If you object to sharing, gently relocate them to wild milkweed patches rather than killing them.

Fungal Diseases

Milkweed can develop leaf spot (circular brown spots on leaves), verticillium wilt (yellowing and wilting despite adequate water), or root rot (sudden plant collapse). Leaf spot is cosmetic—simply remove affected leaves.

Verticillium wilt and root rot are more serious. Good cultural practices prevent most fungal problems: avoid overhead watering, ensure excellent drainage, provide adequate spacing for air circulation, and don’t overwater.

If root rot strikes, it’s typically fatal. Remove and destroy affected plants; don’t compost them. Improve drainage before replanting in that location.

Leggy Seedlings

Seedlings that become tall, thin, and spindly aren’t getting enough light. Move them immediately to a sunnier window or position grow lights 4-6 inches above plants.

Once moved to better light, they may strengthen but won’t become as stocky as seedlings grown with adequate light from the start.

Seeds That Won’t Germinate

If seeds fail to germinate, the most common causes are insufficient cold stratification (needs 30+ days), seeds planted too deeply (need light), incorrect soil moisture (too dry or too soggy), or old seeds with low viability.

Fresh seeds from reputable sources stored properly should germinate at rates of 70-90% if properly stratified.

Transplant Shock

Milkweed hates having its taproot disturbed. Transplanted plants often drop all their leaves and look dead—this is normal transplant shock. The plant is focusing energy on reestablishing roots.

Keep the soil lightly moist (not soggy) and be patient. New leaves typically emerge within 2-4 weeks. This is why planting seeds directly or using biodegradable pots works better than transplanting bare-root plants.

Managing Aggressive Spread

Common milkweed has earned its reputation for aggressive spread through both rhizomes (underground stems sending up new shoots several feet away) and prolific seed production (those fluffy parachutes travel for miles on wind).

Containment Strategies:

Remove seed pods before they split open in late summer. As pods turn brown, cut them off—save seeds for planting elsewhere or sharing with friends.

Install underground barriers by burying plastic or metal edging 12-18 inches deep around your milkweed patch. Or plant in sunken containers—bury large pots or livestock feed tubs with drainage holes and grow milkweed inside.

Pull unwanted shoots as they appear in spring. Young milkweed pulls easily from moist soil. Stay vigilant and remove new shoots weekly until the plant gets the message about boundaries.

Or designate a wilder corner of your property for naturalistic planting and let common milkweed roam free there.

Better yet, choose swamp milkweed or butterfly weed from the start—they stay exactly where you plant them.

Realistic Timeline: What to Expect

- First Growing Season:

Transplants establish slowly, focusing energy on root development rather than visible growth.

Seeds germinate within 1-2 weeks after proper stratification but initial growth is slow. Plants rarely bloom in their first year. Monarchs may still lay eggs on small plants with limited foliage.

- Second Growing Season:

Noticeably stronger growth appears. Common and swamp milkweed often bloom. Butterfly weed may wait until year three for flowers. Monarch activity increases significantly.

- Third Growing Season and Beyond:

Plants reach mature size and bloom reliably. You’ll see substantial monarch activity. Common milkweed may begin spreading if not contained.

Seasonal Cycle:

- Early spring (March-May):

New shoots emerge very late, well after most perennials. Don’t assume plants died over winter—be patient. Some years, butterfly weed doesn’t show signs of life until late May.

- Late spring through summer (May-August):

Active growth and flowering occur. Most species bloom mid-to-late summer. Peak monarch activity varies by region—northern states see monarchs primarily in summer, southern states in spring and fall migration periods.

- Fall (September-November):

Seed pods develop and mature. Plants begin dying back naturally. Late-migrating monarchs may still lay eggs in southern regions.

- Winter (December-February):

All above-ground growth dies back completely. Roots remain alive and dormant, ready to resprout in spring.

Safety Considerations

Milkweed contains cardiac glycosides that are toxic if ingested in large quantities by humans and pets.

The bitter, milky sap generally discourages consumption, but take normal precautions around curious pets and young children. Supervise children around milkweed and teach them not to put plants in their mouths.

Wear gloves when cutting or handling milkweed stems. The sticky white sap can cause skin irritation or allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, similar to latex allergies. If sap contacts your skin, wash immediately with soap and water. Keep it away from your eyes.

Despite the toxicity, milkweed is rarely problematic in gardens. Animals typically avoid it due to the bitter taste, making it naturally deer and rabbit resistant—a bonus for gardeners battling browsing wildlife.

Learn about Harnessing Fig Sap For Natural Remedies, Vegan Cheese & More

Learn about Harnessing Fig Sap For Natural Remedies, Vegan Cheese & More

Creating a Complete Monarch Waystation

Milkweed alone provides larval food but doesn’t create ideal habitat. Adult butterflies need nectar sources throughout their active season, and a diverse planting supports monarchs at all life stages while benefiting other pollinators.

Add nectar-rich flowers blooming in succession: wild columbine and phlox for early spring; purple coneflower, black-eyed Susan, and bee balm for summer; blazing star (liatris) and asters for late summer into fall.

Native plants adapted to your region require less maintenance and support more beneficial insects than non-natives.

Provide a shallow water source—a dish with pebbles for perching or a damp sandy area where butterflies can drink and gather minerals.

Skip all pesticides, even organic products, which can harm monarchs. Embrace leaf damage as evidence of a healthy, biodiverse garden.

Plant densely—a cluster of 6-10 milkweed plants plus diverse nectar flowers creates a more attractive stopping point for migrating monarchs than scattered individuals.

Consider registering your habitat as an official Monarch Waystation through Monarch Watch (monarchwatch.org).

Registration helps document habitat creation efforts, connects you with a community of citizen scientists, and lets you purchase a sign identifying your garden’s conservation purpose.

The Bottom Line

Growing milkweed is one of the most impactful actions a gardener can take for wildlife. Every plant becomes a node in a continent-spanning habitat network.

The monarch laying eggs on your Illinois milkweed in June might be the great-great-granddaughter of a butterfly that fed on California milkweed in March.

Whether you have a window box with two butterfly weed plants or an acre of habitat, you’re contributing to reversing decades of habitat loss.

Your next steps:

Identify which milkweed species are native to your region, order seeds or plants from a reputable native plant nursery, prepare a sunny spot, and plant this fall or stratify seeds for spring.

The monarchs are counting on us—and they’re only asking for a little space, some native plants, and a commitment to avoid pesticides.

That’s a small investment for the privilege of watching one of nature’s most extraordinary migrations unfold in your own backyard.

source https://harvestsavvy.com/how-to-grow-milkweed/

No comments:

Post a Comment